I write long things on small pieces of paper

Or how my neuroses help organize my brain chaos in the writing process

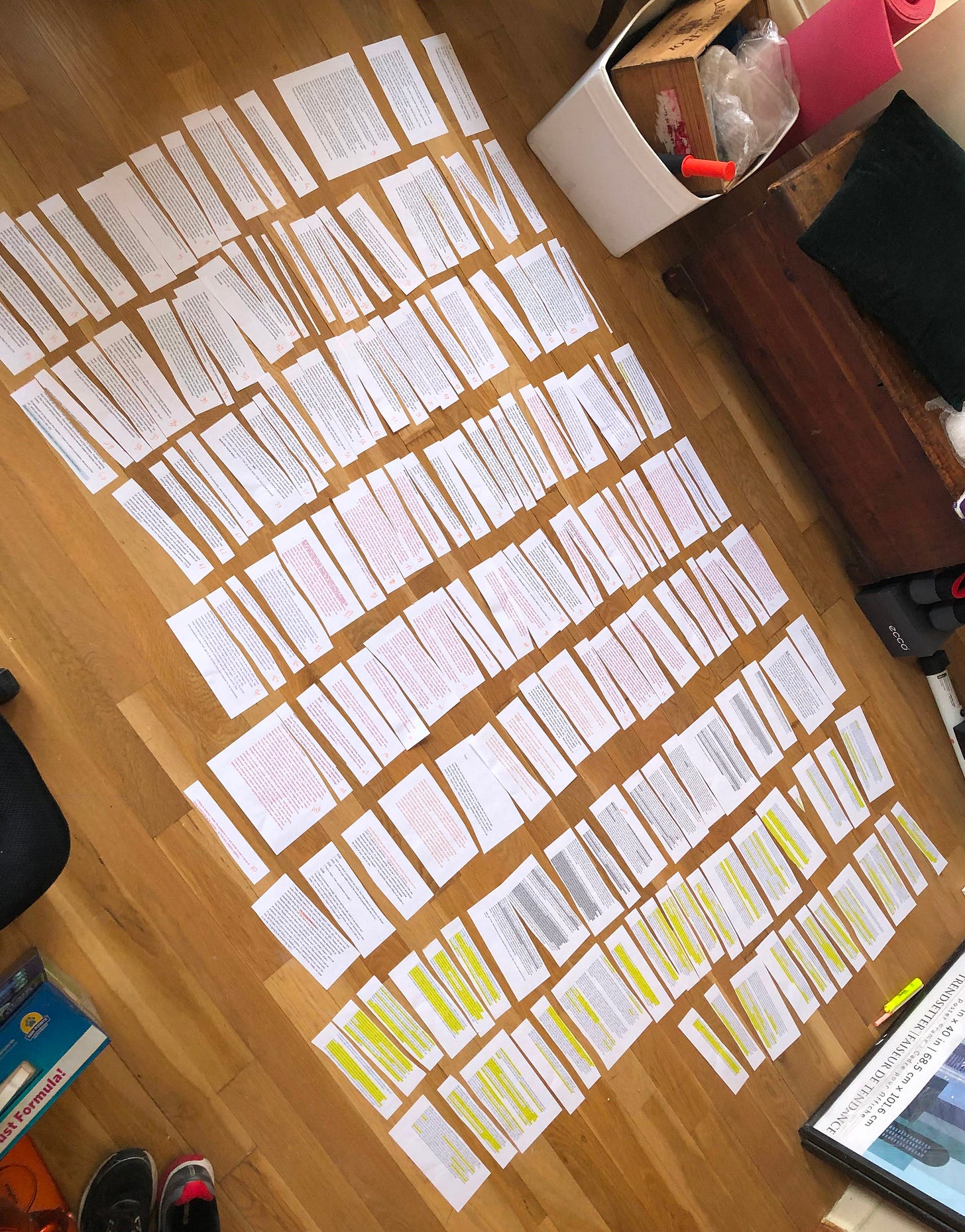

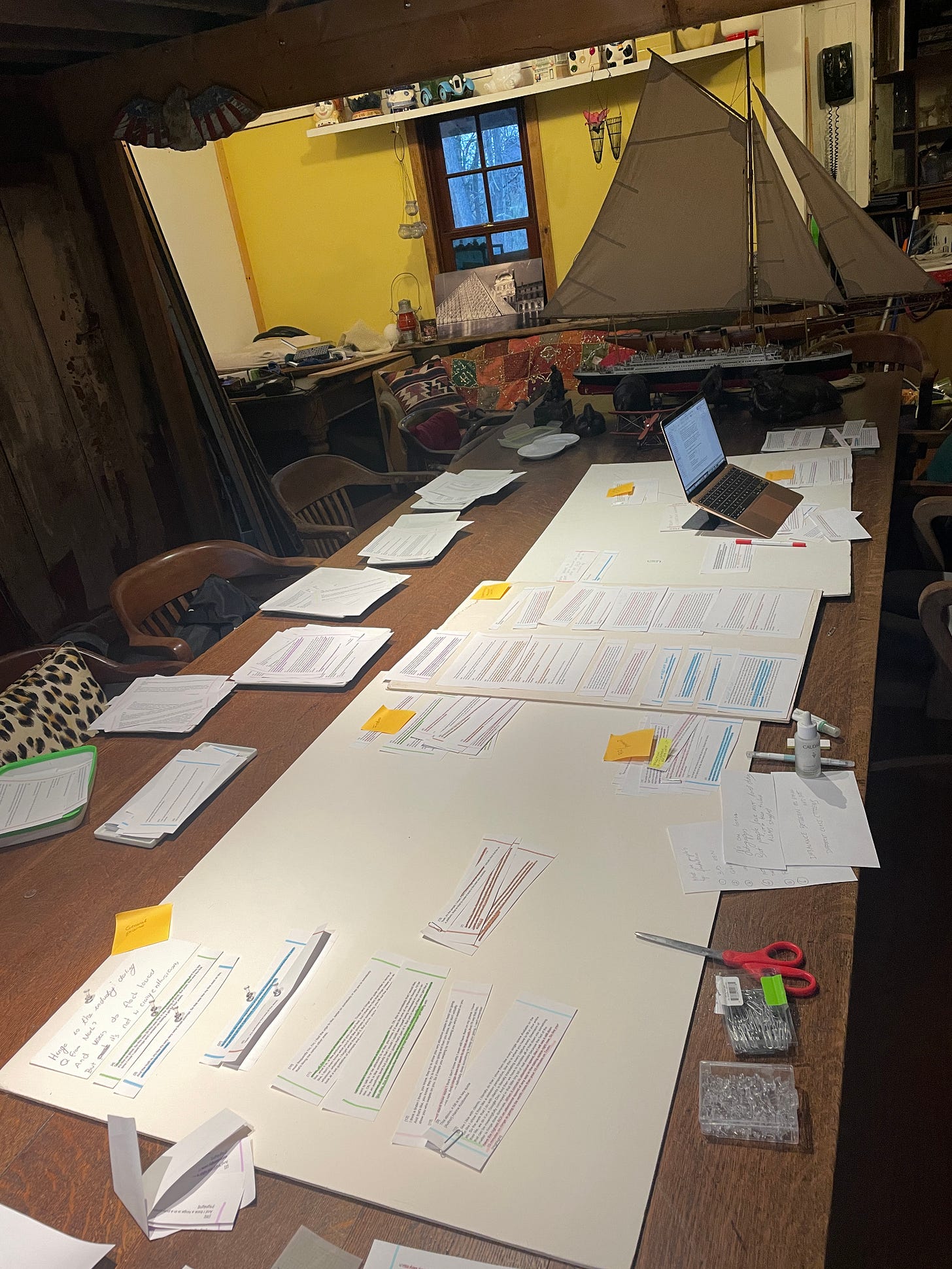

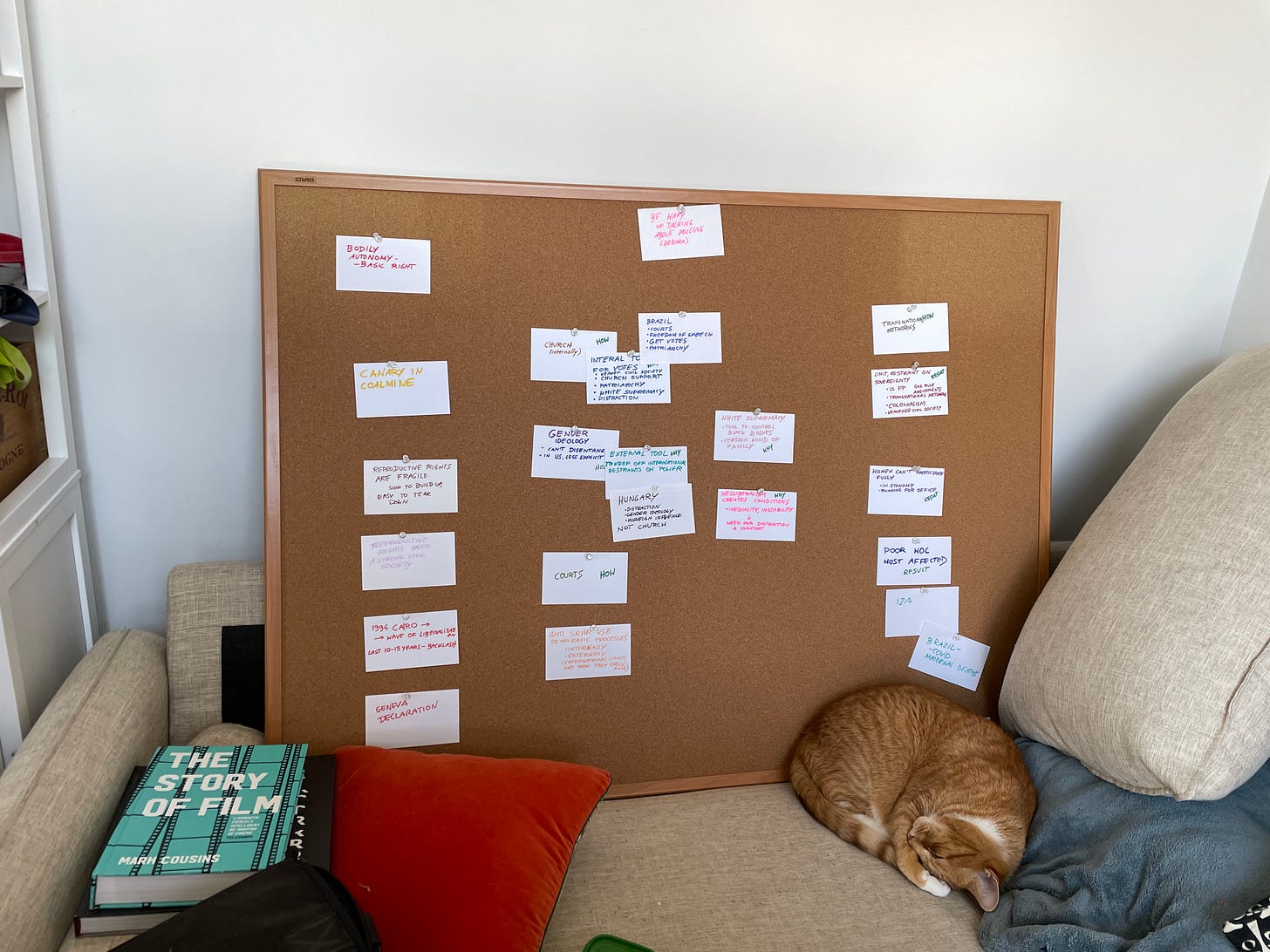

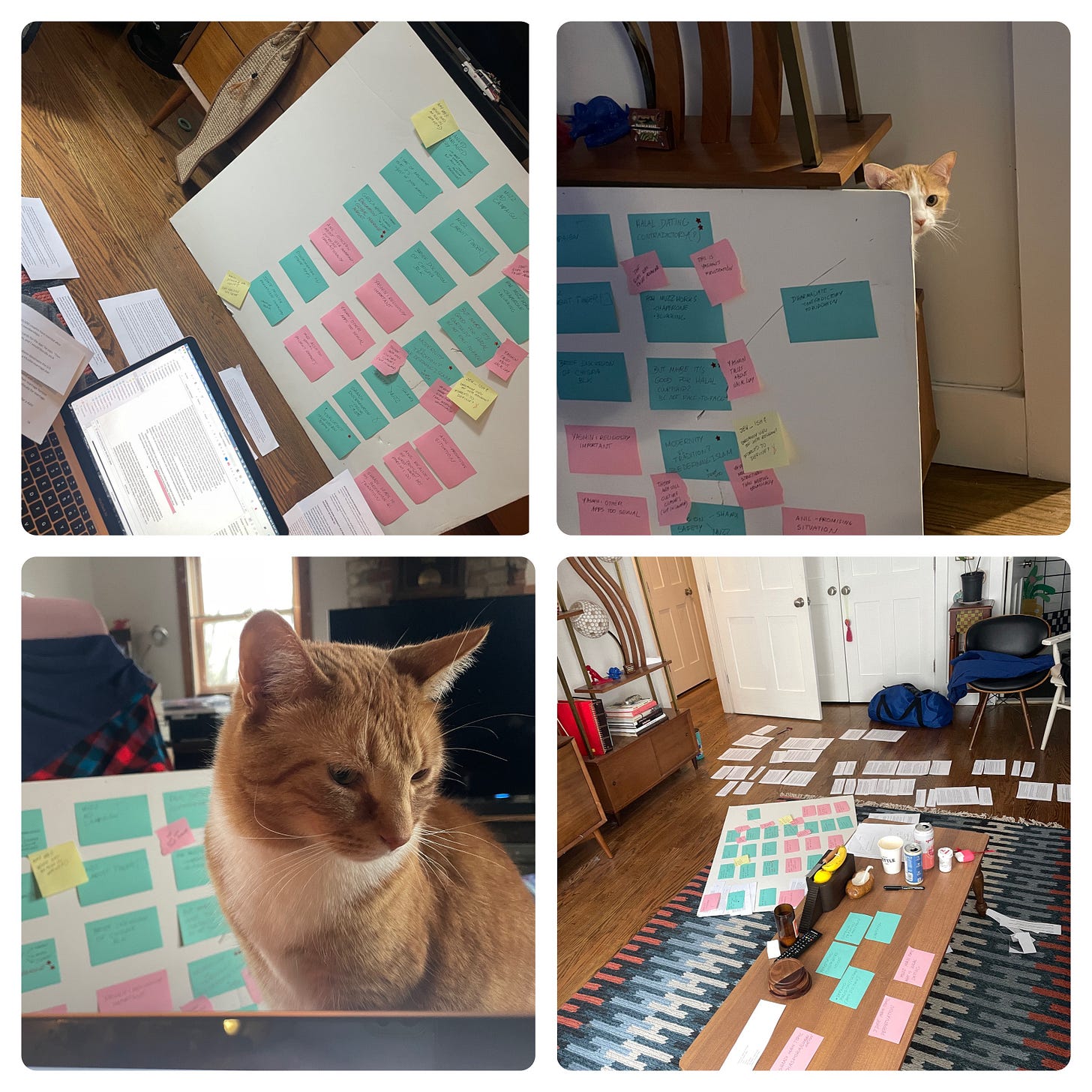

As the tagline of this newsletter suggests, I often write long things on tiny pieces of paper. Sometimes it’s Post-it notes, sometimes it’s index cards, sometimes it’s printed out pages of quotes and research cut up into thin strips. If I’m rich in ink (i.e. have a full time job with an office printer), they are color coded. And they are always arranged on whatever large surface I have access to:

My husband’s expansive cork board, when his own screenwriting projects aren’t occupying it (which is rarely)

The pride and joy of my dad’s life, aka a 13-foot-long heavy wooden table that used to sit in one of Princeton’s libraries. He got it off eBay and had to take down a wall to get it in his house

A foam board I repurposed from my dad’s old architecture models from back when 3D rendering did not exist. I recommend this for its portability, I have put the board in a car and plopped it on a friend’s floor when my work simply could not be left at home

A random piece of thin hardboard that presumably was once the backing for a large frame, also found in my father’s house. The men in my life inadvertently provide me with excellent large flat surfaces for assembling my writing

A floor, if it’s relatively clean.

My work is laid out this way because I must see it all at the same time. I am unable to write long, reported pieces sequentially, filling things in later. I’m also not great at making a typical outline with multiple bullet point types and indents of varying length (or working from one, as evidenced by a writing collaboration where my co-author was an excellent outliner and I a less-than-excellent follower of that outline). Or writing in larger sections and piecing it all together later. I need to see all the little snippets, so I can arrange and rearrange, cut and add like a slightly crazed collage artist.

Even though I can’t outline in the traditional sense particularly well, logic and structure must rule, and they must come first. The flourishes, the flow, the scene-setting, the detail that make the piece come alive will come later. Otherwise I’d be stuck writing and re-writing the first paragraph in an endless, fruitless loop. This way, even if I still do that rewriting 500 times, I know I have the scaffolding for what’s next ahead of me, and not just a messy brain and an empty page.

On the podcast

, the writer compares the process of creating a reported piece to building a house, while writing an essay to something more ineffable. The former is helped by the inner “carpenter” “who knows how to do this well,” while the latter is “opening up some weird portal and trusting that something's going to come through.”Joan Didion (here I go again with the Didion references, sorry!!!) likened writing nonfiction to sculpture:

In nonfiction the notes give you the piece. Writing nonfiction is more like sculpture, a matter of shaping the research into the finished thing. Novels are like paintings, specifically watercolors. Every stroke you put down you have to go with. Of course you can rewrite, but the original strokes are still there in the texture of the thing.

I like these comparisons. Carpentry can still be artful, but it must be practical and sturdy if it’s any good. A sculpture, usually, is contained but malleable.

(In fact, Didion was a proponent of the small pieces of paper method as well. Writer Sara Davidson says that when she was struggling to write a piece in the 1970s, Didion advised her to write scenes on index cards: “Then spread them on the floor and see how you can fit them together, with space breaks in between. Like arranging a patchwork quilt.”)

It is entirely possible someone also told me to use this method, but my memory is terrible. My first recollection of using it was working on a 2400-word dive into the injustice of video visitation in US prisons in 2015. I think it probably started like it starts now: I’ve done a buttload of reporting and research and I’m overwhelmed with all the information. My little gray cells, to quote Hercule Poirot, simply cannot hold it all.

I transcribe all my interviews in their entirety. Usually, there are many of them, at times perhaps too many (thankfully we’re not dealing here with breaking news and usually over-reporting is an asset, not a hindrance). To be honest, I’m not amazing at taking notes when interviewing someone over the phone or on Zoom, I feel like my attention needs to be fully on the conversation. I’m better when reporting in the field, for some reason.

Before the advent of decent automated transcription, I’d use oTranscribe, a web-based software that lets you pause and resume while you type using keystrokes (which I’m linking because sometimes you still want that deep, deep engagement with an interview that you get when you transcribe yourself, or if the background of the recording is noisy or the speaker hard to understand). But this would take hours because I find it extremely difficult to focus on tedious tasks. And Twitter is just sitting there.

Thankfully, these days we have Otter.Ai (or Sonix or TapeACall or Trint or Temi, or, soon enough, just our iPhones?!). I plug all my interviews there, fix the robot’s weird misunderstandings and highlight what I think is important.

I often have a long Google doc with bits of research pasted or typed in there, as well as my own notes that I had written throughout the reporting process (ideally also including anything I’d written in the at least three notebooks I have lying around). It’s imperative that my own notes and someone else’s writing are in different fonts or italics or bold to avoid any accidental plagiarism – a terrifying thought.

(I also have 5,000 tabs at the ready – either open, or collected through OneTab, which has been a lifesaver for many years for someone as, ahem, alternatively organized as I am. I am simply not going to do things like make folders with bookmarks. That’s not me. But if I am disciplined enough with the research on a given day, I can collapse the tabs, lock the list, and label it. Sometimes that works).

Most of the time, I will print all of my material. All the interviews, downloaded from Otter, plus that big Google doc, after some highlighting and culling. If I can, I print in color. If I can’t, I’ll mark every block of text with a different marker or highlighter to know who said it or where I got the info from. I’ll read it all carefully, some shades of structure emerging in my head.

For reported pieces longer than, say, 1500 words, I usually do the strips-of-text method. If I’m particularly stuck on structure, or the piece is idea-heavy but ALSO reported (like this one), after reading all my research and interviews I’ll write each “thing that has to be said,” whether it’s an idea, scene, key quote or theme on a Post-it or index card, so I’m moving bigger pieces of the puzzle around.

There have been times when I’ve had to involve string to connect the pieces across the board, like a deranged conspiracy theorist or network show investigator (I searched for a picture of this for 25 minutes, alas, it’s gone or invisible in the 52,438 photos on my phone).

So what does the patchwork/collage/deranged conspiracy mind map method actually do for me? When I’m looking at my beautiful, satisfying spread I am able to:

Be sure that things flow

Be sure that any connections between ideas, quotes, or scenes are not missed

Be sure that I’m not omitting anything important

Be sure I’m not over-quoting one person

Decide which darlings to kill (Or “babies:” early in my career I misquoted this adage as “kill your babies” to my mentor’s great delight).

And then, staring at my beautiful spread, I write — typing, pasting, polishing. Like a carpenter. Or sculptor.

Naturally, I used this process while writing my book proposal. Several times. I assigned sticky tab colors to chapter descriptions according to their progress. For my sample chapter, I designated blue Post-its for “context/research/ideas” and pink for “character stories,” so I could clearly see how exactly I was interweaving the two. It looked crazy at times, but it helped – as always.

My reporting and writing plan for the next several months is also in poster-board-and-sticky-note form. My research process has to be more organized, a Google doc with that amount of research would work with the speed of Windows 95 — to say nothing of the library of books I’m referencing. I’m doing my best to just input everything into Scrivener folders, which really is as helpful as people say for writing anything longer. Scrivener also has an option to put plan things out on a digital “cork board” with “index cards.” I’m not sure I’ll be able to give up my beautiful spread on a large flat surface borrowed from a dude in my life.

Do you do something similar? Or completely different? Or have tips and tricks? Comment below!

I love seeing people’s creative process! I’m more of a visual artist than a writer (I’d love to learn to write a book sometime but it’s never come naturally to me). I can only do so much on the computer! Tactile methods and being able to see all the information doesn’t hinder my creative process like digital methods do. Also I love your cats! I’ve always been partial to grey and orange cats 🐈 🐈⬛ Here I’ve just started publishing a comic strip about two kitties on a space adventure… I have a script writer and I do the art, but we both contribute ideas to the storyline, and I will have ideas for jokes that I ask them to incorporate into the script and plot. It’s a really fun partnership!

This looks so much fun 😍